The Domestic Role of the Military: Civil-Military Co-operation in Foreign and Domestic Crisis Areas as a Test Case for the Acceptance of the Military in Dutch society

Fred H.M. van Iersel, Desiree Verweij and Erhan Tanercan

Introduction

This year’s JSCOPE conference is about the domestic role of the military. We think that this is a vital theme, especially in the Netherlands. Since September 1999 the Dutch Armed Forces officially has had three tasks[1]. The first task mentioned is to protect the integrity of our national and allied territories (including the Netherlands, Antilles and Aruba); the second task is to further stability and the international legal order; and the third is supporting civil authorities with law enforcement, disaster relief, and humanitarian aid (both national and international).

To execute these tasks the Royal Netherlands Army Doctrine Document describes three kinds of Military Operations. First, there are Combat Operations against either Regular Forces or Irregular Factions (guerrilla’s, rebels, warlords). Second, the document describes Peace Operations. Internationally there are several views on the categorization of Peace Operations. The Royal Netherlands Army distinguishes Peace Operations (PO) in Peace Support Operations (PSO) and in Military Operations Other than War (MOOTW). PSO are Conflict Prevention, Peace Making, Peacekeeping, Peace Enforcement (Post-conflict), Peace Building and Humanitarian Operations. MOOTW are considered to be Humanitarian Operations in non-PSO-scenario’s, military aid/support to civil authorities and Non-combatant Evacuation Operations. The third and last category of Military Operations are the National and Kingdom Tasks such as Security of National Territory, Military Assistance and Support, Host Nation Support and Explosive Clearing.

What we will do in this paper is look at the domestic role of the military--for example in Military Assistance and Support operations--from the point of view of the legitimacy of the Dutch Armed Forces. Apart from the obvious benefit of national defence, one could ask why the armed forces are still widely accepted in the Netherlands. And if the reasons are clear, we should wonder if these proper reasons, which are related to the central tasks and objectives of the military. For reasons of methodology we will start by presenting an analysis of the moral dilemmas of civil-military co-operation in foreign area Peace Operations. From this starting point we will turn to the legitimacy of the domestic role of the military in Military Assistance and Support operations. This will illustrate clarifying contrasts and interrelatedness between the two operational situations. In response to the ethical challenges that will be discussed in this respect, we will introduce the concept of ‘moral fitness’.

1.1 Reasons for civil-military co-operation in foreign crises areas

Before we discuss civil-military co-operation (CIMIC), it is absolutely necessary to define the issue. Many of us are used to speak about CIMIC as if we know what it is. But is this really clear?

CIMIC: a military operation

Let us take the military point of view. From this perspective, CIMIC is not civil-military co-operation. Instead, it is (and now we start quoting): “a military operation which is primarily aimed at and leads towards the support of a civil authority, the population, and/or international organizations and NGOs, which in the end should lead to the fulfillment of military objectives”[2]. We take this from the official Royal Netherlands Army (RNLA) Doctrine Document about MOOTW. Now what is important here is that, first of all, CIMIC as a term refers to a military operation and not to the civil-military co-operation as such. Secondly it is clearly stated that CIMIC is aiming at the realization of military objectives, which implies that it is not aiming at facilitating humanitarian aid by NGOs or IGO’s as an objective in itself. Thirdly it is implied here that CIMIC is a tactical doctrine, not a strategy. CIMIC is about controlling civil actions as instrument in a strategy aiming at the stability and the reduction of security risks for the population in the crisis area.

Concentration

We quote again the RNLA doctrine: “CIMIC implies the concentration of all activities in a crisis area with the aim to prevent that parties in combat restart their hostilities”[3]. Note that there are two remarkable statements made here. Firstly, the objective stated here might well be a legitimate one. The prevention of the restart of hostilities is a legitimate translation of the importance of the security interest of the local population. The second statement implied in the citation we just gave is one about concentration. Many NGOs do not like concentration because of their organizational autonomy, their mandate and their stakeholders’ interests.

Military assistance and humanitarian operations

An essential dimension of CIMIC is what the RNLA doctrine calls military assistance. Military assistance is (we quote again) “supportive action of a peace force, which is being executed after a request from a government or a regional or local authority. Where there is no such effectively functioning authority, military assistance will consist of direct aid to the civil population” [4]. Now here is a phenomenon, which raises objections on the side of NGOs. Why should the military give any direct aid at all? The military’s answer is implied in the RNLA doctrine: because there is no local authority whose functioning can be facilitated and promoted. We think there is one more argument for military assistance. The most important one is in the area of logistics. Humanitarian aid should be given as quickly as possible. Therefore logistics are very important. This is a strength of the military, especially in crisis areas. So the ethical underpinning of the argument is this: the military can help, therefore it should do so.

Protection of aid workers

Now any military involved in a CIMIC operation also plays a protective role. But the protective role is a limited one. We quote again the RNLA doctrine. “The protective role during a relief providing operation especially relates to the protection of the military performing relief tasks, the aid providers of other NGOs and the protection of goods. The protection of relief workers of other international organizations (including the UN) is considered to be primarily the responsibility of the local authority. However the local authority is not always able or willing to protect these relief workers. If the Armed Forces should have a task here it should be included in the mandate and the Rules of Engagement” [5]

This might present a problem from the point of view of humanitarian international organizations, in two ways. First, they might expect the military to protect them in some way or another, when this is not stipulated in the rules of engagement. Or, on the other hand, they might prefer that the military not be present in the crisis area at all. Apparently neither is the case at the level of CIMIC doctrine.

Legitimacy of foreign area Peace Operations

Having completed this short sketch of aspects of the CIMIC definitions and doctrinal dimension, we will turn to its legitimacy. Why should there be CIMIC at all? We think there may be severeal reasons.

The first reason is rooted in the nature of contemporary conflict. If a third party is involved in a contemporary intra state or regional conflict, it is more often than not being confronted with the consequences of a failed state and a weakly developed civil society. Certainly in the context of post conflict peace building, both the state and civil society need to be re-built. In the end however, any external intervention--whether civil or military--can only play a temporary, supportive role, which is based on the principle of the subsidiary functioning of different levels of society and politics[6]. This principle entails that “a community of a higher order should not interfere in the internal life of a community of a lower order, depriving the latter of its functions, but rather should support it in case of need and help to co-ordinate its activities with the activities of society, always with a view to the common good”[7]. Even when it comes down to a temporary military dominance and foreign political and legal rule as in the cases of the international military presence in former Yugoslavia, this principle of subsidiary functioning should work as a motivation for a strategy of empowerment of the local population.

This principle of subsidiary functioning of different levels of society and politics implies both supportive commitment and empowerment of the local population in a crisis area and the timely withdrawal from the area. The local population and the local authorities should be committed to all the dimensions of the peace building process as soon as possible and as much as possible. We think here we find a common challenge both to the military and to humanitarian organizations: not to (re-)colonize an area, but to strengthen the local capacities for peace and for humanitarian relief as much as possible and make themselves superfluous as soon as possible. In practice this principle of subsidiary functioning turns out to support both the presence and the exit-strategy not only for the military and for international organizations, but also for NGOs.

1.2 Ethical Challenges in foreign area Peace Operations

We now turn to the second part of this section, the challenges in the context of civil-military co-operation.

The first challenge regards the search for a balance between the core businesses of both types of organizations. Whereas the military has security as its core business, humanitarian organizations find their strength in the field of aid. In fact humanitarian organizations presuppose the security provided by the military. Secondly, the military and humanitarian organizations have a different forum for their accountability. Whereas the armed forces always accountable to their government, parliament or the IGO they are part of, the humanitarian organization primarily accountable to their civil supporters at home. The third area of difference regards the different mandates. With regard to the quality of the mandates we think the dynamics of the functioning of the military will always be determined by politics and its policies--which by the way gives it a democratic legitimacy--whereas NGOs represent a different type of mandate, namely a self-given one which has been reaffirmed by only a part of the population at home. This difference will always present a tension to civil-military co-operation in any future we can foresee.

We believe NGOs should develop a kind of ‘doctrine’ for civil-military co-operation from their side, hopefully not apart from each other, but together with partner organizations which are likely to be active in any given certain crisis area. In such a ‘doctrine’ the principles for civil-military co-operation should be spelled out. Such a doctrine should also provide the common responsibilities of civil organizations and armed forces. We see at least two of these common responsibilities. The first is the respect of the basic rights of the population in a crisis area, including the right to be given aid if it has become necessary. The second basic right of the local population in a crisis area is that aid is given in such a way that the capacities for self-help and the capacity for self-organization and political participation are being promoted instead of being undermined by the given aid. The acceptance of these principles may keep both the military and humanitarian NGOs away from a too high degree of intervention. The principles may help them to turn away from a shareholders approach to a broadly defined stakeholders’ approach. Such an approach is not only based upon a moral appeal. It is about self-interest as well. The strengthening of the local capacities for peace, self-help and self-organization will, in the end, increase the effects of our own efforts. And it helps to define exit-strategies both for the military and for NGOs. Moreover, the fact that such an approach implies a more efficient way of using both public and private resources makes the accountability to those at home much easier.

We also see a fourth difference between the military and humanitarian organizations. It is in the specific means they use to accomplish the ends of civil-military co-operation. The use of force especially raises resistance on the part of NGOs to co-operation, due to the clashing attitudes towards it found in the professionals of both the military and the NGOs. Of course the military has a legitimate use of force as a main characteristic. And of course, the legitimate use of force by the military also demands the acceptance of different types of professional risks, which leads to different entrance and exit strategies. On the other hand, humanitarian NGOs are supposed to refrain from force, even in an insecure situation which would make self-defence in itself appropriate.

As a consequence, there is a huge difference between the situations in which the military and NGOs perform their core business. For the military this is a situation defined by a lack of security. Security is the absence of uncontrolled risks. If there is no security at all, then it appears that all activities in a region are determined by the lack of this basic human need, including aid activities. And here is a main challenge for NGOs: to recognize and acknowledge security as an ethically legitimate basic human need[8].

Within humanitarian NGOs very often there is a pacifist impulse, which is based on the respect for human life as an intrinsic value. However, does not pacifism presuppose a sovereign state that is able to guarantee the security to its citizens? Any realistic type of pacifism should include solidarity with the unprotected people, who are often betrayed by their own governments, especially in weak states. Therefore the pacifist impulse within humanitarian and political NGOs should focus on the level of armament and the types of weapons involved in conflicts, rather than to deny the need for security for those who cannot defend themselves. In other words, we would say: ethically speaking pacifism is one of two ethically legitimate positions. But pacifism should not underestimate the power of ‘evil’[9] and the need to limit its impact as a threat to the security of the unprotected[10]. Here is the main reason why the pacifist opposition against the role of the armed forces in the Netherlands has been crumbling over the last ten years. Meanwhile, pacifism in the Netherlands to a high degree is a movement of solidarity with victims of armed conflict. The historical reason for this is that the leading Dutch peace organizations largely were established immediately after World War II, which implied a successful intervention in the victimized Netherlands. This has had a paradoxical effect: the Dutch peace movement frequently pleads for military intervention in cases where many in the military argue that such a military operation will only be successful under strict conditions.

We think most of us present at this conference will agree that such a protection of the vulnerable is a moral value in itself. Our opinion is that, in addition, this protection should sometimes be accompanied by humanitarian aid, aid delivered by the military, both for practical reasons and also as an expression of the respect for the human dignity of the local population. The reason for this opinion is based on an analysis of the ethical differences between traditional wars (Combat Operations) and Peace Operations which one of the authors of this paper published recently.[11] It appears that, among other things, the legitimacy of Peace Operations is far more complicated than the issue of the legitimacy of a traditional war for self-defence.

|

|

Combat Operations |

|

Peace Operations |

|

1. |

High frequency of known and controllable situations |

1. |

High frequency of new type of situations |

|

2. |

Well developed doctrines |

2. |

Doctrines still in a developmental stage |

|

3. |

International law is well-codified |

3. |

International law has many lacunas (e.g. status ROE) |

|

4. |

Military penal law is easily applicable |

4. |

Military penal law does not acknowledge an apart status for new ethical dilemmas for the military |

|

5. |

Instructions regarding the use of force express the nucleus of the military profession |

5. |

Instructions for the use of force is similar to that of the police |

|

6. |

Presence of a well developed ethics (Ius ad Bellum, Ius in Bello) |

6. |

Ethics is still being developed: there is no “ Ius ad Pacem” or “Ius-in Pace” for PO |

|

7. |

Military organizations are organized for war |

7. |

Military organizations still are less well built for PO situations (e.g. the use of aid supplies) |

|

8. |

Heavier weapons are being used |

8. |

More relatively light weapons as equipment |

|

9. |

Combatants can be killed on a legitimate basis |

9. |

Soldiers act less legitimately when for killing |

|

10. |

Self defence has a legal status in national law |

10. |

PO often are built on less and weaker legitimacy in national laws, politics and public opinion |

Ethical differences between (defensive) Combat Operations and Peace Operations

(C) AvIersel

Because of the more complicated nature of the ethical legitimacy of PO, in our opinion, respect should be given to those working to guarantee or establish the security, namely the military. The legitimate use of force by armed forces from democratic countries should not function as an alibi for humanitarian NGOs to refuse co-operation. Nor should humanitarian aid provided by the military on either side be considered as an example of mission creep; instead, NGOs should be realistic enough to see that humanitarian aid increases the legitimacy of an intervening military power, especially when it is not primarily intervening for reasons of self-interest, and provided the basic rights of the local population are being respected as we mentioned them earlier.

On the other, side the military deploying in a crisis area should acknowledge that peace is not only a matter of imposed security. Instead, a stable peace should have a “voluntary” basis as well: it should be based on the will to live in peace. However, the will to live in peace cannot be enforced; if ‘third parties’ can influence it at all. It can only be stimulated by civil activities. Therefore, the military needs NGOs committed to peace and humanitarian aid, and sustaining the human dignity of the population, in a crisis area. Apart from that, humanitarian aid can also function as a means for stabilizing a conflict region.

The lacunas with regard to the legitimacy of PO bring about new ethical dilemmas for all actors involved. And it is only natural that not all players have dealt with these dilemmas similarly and find solutions in synchronic processes. CIMIC is especially relevant to PO: however it is also one large source of new dilemmas for all actors involved. Therefore we think it is necessary to develop a type of ‘dilemma sharing’. This involves first of all common training for coping with ethical dilemmas and with tragedy. Secondly, dilemma sharing also implies a sharing of ‘lessons learned’ in the area of civil-military co-operation. We would suggest doing some common evaluative case studies together with NATO and the EU. Thirdly we would suggest the search for appropriate common codes of conduct. Maybe NGOs should be included in policy development of the military on a more systematic basis, if circumstances allow a longer period of time for preparation.

There is still much work to do. For example, changes are needed at the level of organizational cultures and professional ethics of the professions involved. In the end the most important thing to do is to turn towards an approach in which the local population in a crisis area is regarded as the cornerstone of any enduring solution to its political, military and humanitarian problems. So one of the most important things to do in the short term is to study under which conditions a strategy of empowerment, especially in a post conflict situation, can be a shared ideal for the military and the NGOs. This presupposes a widely spread support for internationalism in the Dutch population. This does indeed exist. Also opinion polls show the Dutch population is inclined to consider the local population in a crisis area as a stakeholder in Peace Operations.

2. The Domestic Role of the Military

2.1 The Domestic Functions

A first possible role, domestic police actions by the military, has been substantially restricted in the Netherlands since the armed forces broke a great railway strike in 1903. Since 1903 the term ‘police actions’ for military activity is avoided: the Dutch population did not accept the armed forces fighting against itself. It is not very likely that the armed forces will develop a new role in domestic policing.

Avoiding the use of policing was reinforced considerably through the Dutch experience during the de-colonization of Indonesia (1945-1949). The Netherlands fought against the de-colonization in what were called police actions; nevertheless the end result was the recognition of Indonesian Sovereignty by the Netherlands on December 27, 1949. Originally this de-colonization war, fought against the Netherlands, was regarded as “domestic” troubles, with the armed forces in a police role. Therefore, as far as police action is concerned, there is a sharp contrast between the domestic role of the military in the Netherlands and recent foreign roles of the Dutch armed forces in Peace Operations, which might be characterized as police actions as well.

Since 1949, only the fall of Srebrenica has had an impact comparable to the de-colonization of Indonesia. The fall of Srebrenica (1995) had a huge impact on the willingness of the Dutch population to engage in (foreign) police actions, especially when it comes down to formulating conditions for commitment. We suggest that the fall of Srebrenica perhaps has confronted the Dutch population with the tragic consequences of “neutral” internationalism amidst violence. Both the population and politicians tend to regard all Peace Operations as primarily military. It is common sense that all police actions should be based on military capacities in the first place and that the central task of the military is to “manage violence”, but only as an answer to primarily “external threats,” which sometimes become apparent in internal conflict, for example in the war on drugs.

These developments have resulted in a recent change of the Dutch Constitution. It now confirms that the military has a role both in national self-defence and in the maintenance and implementation of the role of law in international relations. The conditions for commitments to this type of police actions, however, are still being discussed.

2.2 The legitimacy of the actual domestic roles

At the moment the Dutch Armed Forces basically fulfill two types of domestic functions. The first one is crisis prevention and relief; the second is an educational role.

The legitimacy of these roles was discussed in 1998 in a public “strategic defence debate” which was started by the Dutch Minister of Defence. The Minister proposed not only to institutionalize the role of the Armed Forces in domestic CIMIC operations aiming at disaster prevention and disaster relief. Also he presented the idea of an educational role for the armed forces, especially for young people who already lost several social opportunities. As a result of this, the Armed Forces started several school projects for people with, e.g., language or social deficiencies. In this paper we want to elaborate on this educational role. It is not an official task of the Armed Forces. But is an essential instrument in acquiring and keeping young personnel. And as such it is a very important means of operation within the Dutch labour market. (See: the Defence report page 82/83 of the Dutch text). Ethically speaking, this educational role is a somewhat ambiguous phenomenon. On the one hand, it is accepted by the Dutch public and politicians that the professional armed forces have to be active in finding personnel at the youngest possible age, and that one strategy to reach this aim is offering education (in December 2000 for the first time ever a military schooling has been certified by the Ministry of Education). Besides, the offer of education might be helpful to the integration and emancipation of minorities in the Netherlands. On the other hand, the world-wide combat against child soldiers has led to a parliamentary majority demanding a “straight eighteen” entrance to the Dutch armed forces. Of course this interferes in the realization of a planned educational role of the military. Therefore one could state that, although the legitimacy of the educational role has been accepted, its implementation is complicated. This is exacerbated by Dutch public opinion, which shows a paradoxical combination of constantly high support for foreign military commitment and an equally consistent hesitation as far as the entrance of its own youth in the armed forces is concerned, due to the fact that this youth will be sent to (foreign) crisis areas to risk their lives.

During the Strategic Defence Debate, The Minister’s position on the domestic role in crisis prevention and relief has hardly been discussed. Every Dutchman knows the image of soldiers working to save the dikes. Of course everybody knows that soldiers are at risk in such situations. But this was considered an acceptable risk. No one, however, will regard saving dikes as the highest priority of the Dutch armed forces. The domestic role of the military can even lead to odd tasks for military units, like “Millennium Assistance” or assistance to the clearance of pig-farms because of the “pig-plague”. One can question if assistance to, e.g., the Eleven cities tour (Elfstedentocht) in Friesland, a victim-memorial pop-concert in Enschede or the Four Days Marches in Nijmegen can be considered as military tasks as described in the RNLA Doctrine Document. We think these are examples of the grey area between domestic tasks and Public Relations.

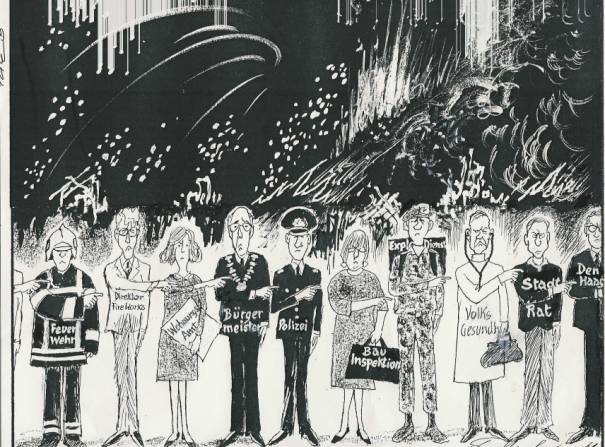

Recently one of these domestic tasks put the Military in a awkward position. On May 13, 2000 a major disaster occurred: fireworks exploded in the city of Enschede SE. A complete district was wiped out, 22 people were killed, and the costs were enormous. After the initial shock, the authorities started to blame each other.

Cartoon by Fritz Behrendt [12]

The defence bureau that advises local authorities on environmental licenses seems to have been unable (due to lack of money and of time) to execute all the necessary checks on the firework companies. The commander (a major) has been sent home on sick leave since the incident. An inquiry committee has researched the disaster and the role of all the parties. The report will appear on February 28, 2001. Here too, one can question if controlling firework companies is a domestic task of the Military. It can of course be considered as disaster prevention, but it does not necessarily have to be carried out by the Military. On the other hand, the acceptance of a professional Military may perhaps be enhanced by the fulfillment of this type of tasks.

3. Responding to the ethical challenges: Moral fitness as a key factor

Peace Operations and the domestic role bring up new ethical challenges. In the following part of our paper we will go into one of the ethical assumptions that in the near future may play a key role in ethical education in the Dutch military. All soldiers involved will need a professional attitude, which prepares them for acting in these new situations. For this purpose, the formation of good moral character is absolutely necessary. This need is analogous to the need for forming the type of character required in the context of POs. How can this formation of moral character be realized? How can we learn to cope with all these different dilemmas in the best possible way? We are dealing here with questions that are often discussed in many military organizations. As a contribution to this discussion we would like to introduce the term ‘moral fitness’.

3.1 The analogy between physical fitness and moral fitness

Education and training play an important role in moral development. However, how can the effect of training and education be measured? Straight A’s for ethics tests and papers are no guarantee for morally just behaviour. Moreover, morally just behaviour is not something that is only tested once. It is something that needs to be displayed whenever it is required and the circumstances that require this behaviour have to be identified as such by the person who has to display the behaviour. Because of this omnipresent requirement for moral knowledge, and the ability to display morally just behaviour in circumstances that require this, the term ‘moral fitness’ seems appropriate. ‘Moral fitness’ seems an adequate term because it refers to a necessary alertness on a moral level. Being morally fit seems the only guarantee that in confrontation with moral dilemmas one can make a morally just decision.

In order to explain the term ‘moral fitness’ in more detail we would like to draw attention to the analogy that exists between physical fitness and moral fitness. Like physical fitness, moral fitness also implies regular training in order to stay in shape. Moral fitness is not something that can be won once and for all; it requires a continuous reflection on the values and norms one lives by and is confronted with, reflection on what to do and how and why it should be done. And if one is in good shape one has to make sure to stay that way.

As with physical fitness, moral fitness also requires checks and evaluations to ascertain one’s fitness. This implies that there are standards one has to meet. As with physical fitness these standards are not just one’s own standards. Although the fitness of persons differs, and fitness has an irrefutable subjective aspect, there are more or less objective standards one has to live up to in order to be called ‘fit’. In this respect it is important to ascertain who decides what the standards of moral fitness are. Also, there is the necessity to make sure there are no double standards. Everyone has to be subjected to the same moral test.

As with physical fitness, moral fitness is also a process; there is no farthest point, it is ‘working toward’, it is a continuous effort to improve on the performances of the past. For this reason moral fitness requires dialogue and debate, openness and transparency, integrity and a willingness to correct oneself.

The analogy between physical and moral fitness can be further illuminated by the relationship van Dantzig describes between physical health and mental health. Physical health gets more attention than mental health; we seem to be more focused on physical hygiene than on mental hygiene. There is an interesting parallel: we pay more attention to physical fitness, in contrast with moral fitness. Van Dantzig has described the absence of care for mental well being in several publications. It is the central theme of his book ‘Is alles geoorloofd als god niet bestaat?’(“Is everything allowed when God does not exist? “) . In it Van Danzig pleads for a responsible mental health care in which we “learn to take care of our souls in the way we have learned to take care of our teeth”. We don’t seem to be familiar with this way of taking care of ourselves. However, this doesn’t mean that there is no need to commence. In accordance with this critique on the singular focus on the body and the plea for an equable share of our attention and care for our physical and mental well being, we suggest trying to strive after moral fitness in the way we strive after physical fitness.

3.2 Moral fitness: a ‘classical’ concept

Moral fitness is an appropriate term for the moral attitude that is needed in our post-modern time. It points to the attitude of a person who can cope with the increase of ethical questions and dilemmas, because he or she has the necessary moral alertness that is required. Moral fitness implies that a person regularly practices critical self-reflection.

However post-modern the concept of ‘moral fitness’ may be, it is related to the ethical tradition of the past. To be more precise, it is related to Aristotelian ethics. Moral fitness implies what Aristotle called ‘phronesis’ and ‘virtue’. ‘Phronesis’ can be translated as ‘prudence’, ‘practical insight’ or ‘practical wisdom’. Aristotle defines ‘virtue’ as a state of character concerned with choice. It is practical wisdom that makes it possible to make the right choice: the choice that lies in a mean between two vices, one which depends on excess and the other which depends on defect. So virtue is the ability to choose the ‘right mean’. This is a disposition that is acquired by habit. Aristotle states that “ . . . moral virtue comes about as a result of habit, whence also its name (ethike) is one that is formed by a slight variation from the word ‘ethos’ (habit).” (Aristotle, Ethica Nicomacheia, Kalias, Amsterdam 1997. Translated and elucidated by Ch.Hupperts and B. Poortman.)

Aristotle explains the term ‘right mean’ in the following way: he points out that there are certain qualities that can be nullified both by defect and by excess. This holds for instance for physical power and health. Too much as well as too little physical training affects physical power. In a similar way both excess and defect of food and drink corrodes health. Only the ‘right mean’ results in physical power and health. One of the examples Aristotle discusses is ‘courage’, being the right mean between fear and recklessness. Correspondingly every virtue is the ability to find the ‘right mean’. This ‘right mean’ is always the right mean in relation to us, Aristotle states. He illustrates the meaning of this statement with the example of the amount of meat an athlete should eat. If ten pounds of meat is considered too much and two pounds is considered too little, the mean is six pounds. However, Aristotle points out, a trainer will not, without due consideration, prescribe this mean to every athlete. He will have to determine the right amount for every individual. In other words, finding the right mean implies finding our own right mean.

The term ‘moral fitness’ fits in an Aristotelian framework. Firstly, it is interesting to notice that Aristotle uses the analogy with physical concepts to explain moral concepts. For instance: physical power and health, physical training and the amount of food athletes eat. Secondly, according to Aristotle virtue has to be demonstrated in action. In other words, virtues have to be put into practice. Thirdly, Aristotle explicitly states that virtue is a state of character that can be acquired by habit. In other words, one has to work on it. Fourthly, virtues have a subjective, but also an objective aspect. Aristotle discusses the mean in relation to us, but the ability to choose this mean requires practical wisdom.

On the basis of Aristotle’s ethics ‘moral fitness’ can be described as having practical wisdom. This means that one is able to find the right mean between two extreme positions. This illustrates one’s virtues. Virtues contribute to a good and flourishing life. At the end of the Ethica Nicomacheia Aristotle points to the Politica, his book on politics, which he considers a continuation of his book on ethics. To Aristotle ethics and politics are connected. That is understandable because Aristotle is convinced that a flourishing life, the realisation of which is discussed in the Ethica Nicomacheia, can only be fully realised in a political community, a polis. What connects the members of a polis is a shared ideal of a good and flourishing life. The political community is the place where virtues can grow. Thus, a community of persons can foster moral fitness among its members. For the military community, this implies a thorough understanding, application and practice of the values and virtues that are vital to the military in a free and democratic society.

Two of the most important values, or principles, in this respect are accountability and responsibility.

3.3 Accountability and responsibility

In our opinion, moral fitness for the military must be grounded in accountability and responsibility, which are twin pillars upholding the functioning of the military in a free and democratic society? Accountability is a vexing concept for theorists across a broad range of disciplines. It is often ill defined and erroneously merged with the allied concept of responsibility. Accountability is the mechanism for ensuring conformity to standards of action. In the military, this means that those called upon to exercise substantial power and discretionary authority must be answerable (i.e., subject to scrutiny, investigation and, ultimately, commendation or sanction) for all activities assigned or entrusted to them. In any properly functioning system or organization, there should be accountability for actions, whether those actions are executed properly and lead to a successful result or are carried out improperly and produce injurious consequences.

In peace operations, even though military personnel are technically accountable to their immediate superiors in the chain of command, media intensity can focus public attention. This then leads to public scrutiny. Thus soldiers and officers may find themselves called up to account for their actions (or in action) before civilian inquiries.[13]

The term responsibility is not synonymous with accountability. One who is authorized to act or exercises authority is ‘responsible’. Responsible officials are held to account. An individual who exercises powers while acting in the discharge of official functions is responsible for the proper exercise of the powers or duties assigned. As mentioned above, in peace operations there are a wide range of responsibilities. Military personnel may become responsible for the well being of the host population and for a wide delivery of services from protection to humanitarian relief.

Concluding remarks

We think that the acceptance of the Military in the Dutch society can be strongly supported by CIMIC-operations in foreign and domestic crisis areas. But people want to be proud of their men and women, their sons and daughters, in Peace Operations as well in the National and Kingdom Tasks. So the Military must do the right things and be prepared to make morally right decisions. Co-operation with civil parties, training with them and understanding them, is unavoidable and vital. And finally we should train ourselves and our people to be morally as fit as possible.

This paper expresses only the opinions of the authors:

Prof. dr. A.H.M. (Fred) van Iersel is a staff member for military ethics. At this moment he is especially working on a project for quality assessment of ethical dilemma training for the Dutch Minister of Defence. He also holds the Chair for Military Chaplaincy at the Tilburg University. The Address: Post-box 9130 5000 HC Tilburg, Tel 0031134662538, e-mail address: a.h.vanIersel@kub.nl

Dr. D.E.M.(Desiree) Verweij is associate professor in philosophy and ethics

at the Royal Netherlands Military Academy in Breda.

E-mail address: DEM.Verweij@mindef.nl

Lieutenant-Colonel drs. E.C. (Erhan) Tanercan MED is senior staff-officer at the Royal Netherlands Training Command in Utrecht.

E-mail address: lct@chello.nl