The

Evolution of Ethics as a Course of Instruction

Within

the Non-Commissioned Officer Education System

By

CH

(MAJ) Mark R. Johnston

United

States Army Sergeants Major Academy

Fort

Bliss, Texas

December

2008

Outline

Introduction and Purpose-Why We’re Teaching Ethics

I. Some

History-Where We’ve Been

II.

Transformation of NCOES and the Study of Ethics-Where We’re Going

Conclusion

Bibliography

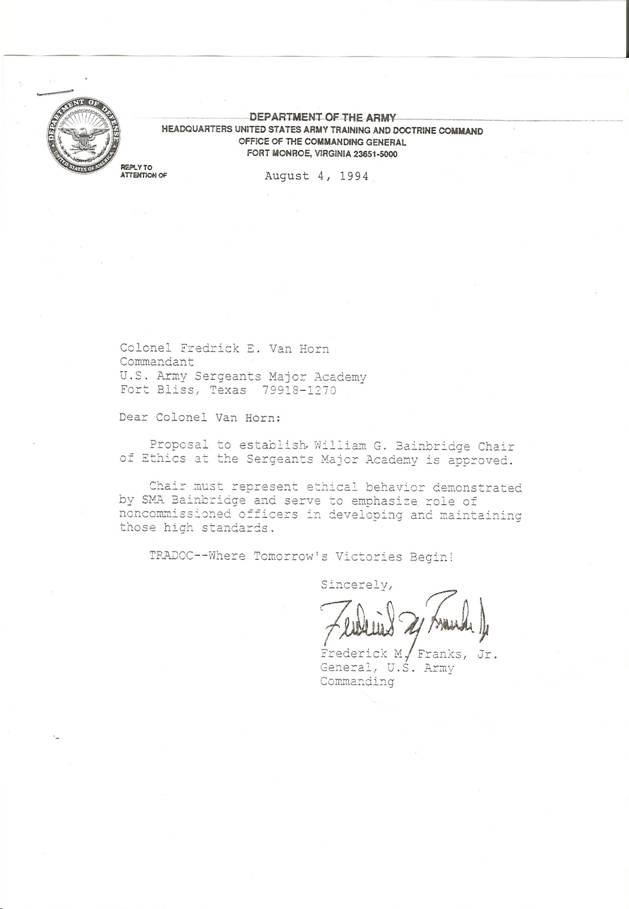

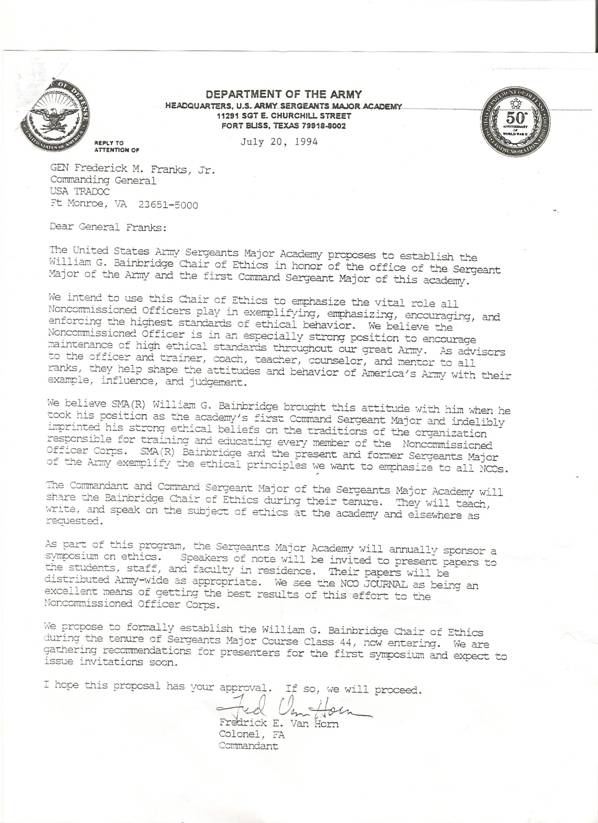

Appendix-Colonel Fredrick Van Horn and General

Frederick M. Franks, Jr. Correspondence

Introduction and Purpose- Why We’re Teaching Ethics

One

month before the American public voted to elect the 44th President of the

United States, Newsweek published a

series of moral questions targeting some of the more important ethical issues

the incoming President will be compelled to engage as Commander-in-Chief. Of

special interest to American military personnel are the two following

questions;

[1]

A)

Does the United States have a moral obligation to act, alone or in concert with

others, when governments manifestly fail in their

"duty to protect"?

B)

Is the first use of armed force ever morally justifiable?

These

questions have significant implications for both diplomatic and military

strategy. No one understands this better than the uniformed personnel serving

in the American military. As this nation continues to be confronted with

persistent conflict[2]

or what the Bible terms as “wars and rumors of war” throughout the world,[3]

men and women are increasingly placed into ethical dilemmas driven by the

larger moral issues posed above. That the United States will continue to engage

in military action seems certain as the global “flattening” of the world

continues to occur.[4]

Because of this, interest in the study and teaching of ethics within the

Non-Commissioned Officer’s Education System (NCOES) remains an important

subject for consideration.

Military

ethics helps to anchor the ‘management of violence’[5]

within the realm of hope for a more civilized and humane world. Values, morals

and faith often contribute to the defining of personal and institutional

behaviors.[6] In

a world where competing value systems can quickly fade into moral colorlessness,

the effort to standardize the content and method of teaching ethics remains a

priority within NCOES.[7] Military

ethics provides the professional and rational framework for pulling the trigger

and taking another human life.[8]

Ethics also becomes a factor in the psychological well-being of soldiers who

must kill in the line of duty.

It is the purpose of this paper to

briefly examine the teaching of ethics to E8s and E9s within the NCOES, as

represented by the United States Army Sergeants Major Academy (USASMA). [9]

This will be done by briefly examining some of the evolutionary history of

USASMA’s ethics instruction and the current transformation of educational

modules to meet the demands of the future force. [10]

I. Some History-Where We’ve Been

Ethics

training and education is a relatively new discipline of study at USASMA. Some

22 years after the founding of USASMA,[11]

a chair in ethics was initiated. In 1994, under the leadership of the

Commandant of the Academy, Colonel Fredrick E. Van Horn, a letter written to

Frederick M. Franks, Jr., the Commanding General of the United States Training

and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), proposed the establishment of the Chair of

Ethics in honor of the Sergeant Major of the Army and the first Sergeant Major

of the Academy, William G. Bainbridge.[12]

The

Bainbridge Chair in Ethics, as it was to be called, would “emphasize the vital

role all Noncommissioned Officers play in exemplifying, emphasizing,

encouraging, and enforcing the highest standards of ethical behavior.”[13]

The proposal included the role of the Commandant and the Command Sergeant Major

of the Sergeants Major Academy to serve as co-chairs of the Bainbridge Chair of

Ethics during their tenure at the Academy with responsibilities to “teach,

write, and speak on the subject of ethics at the academy and elsewhere as

requested.” Additionally, an annual symposium on ethics would be sponsored

through the Academy with “speakers of note who will be invited to present

papers to the students, staff, and faculty in residence.” These papers would be

distributed army-wide through media such as the NCO Journal which was viewed as

an “excellent means of getting the best results of this effort to the

Noncommissioned Officers Corps.”

The

vision of Colonel Van Horn was based on the conviction that the

“Noncommissioned Officer is in an especially strong position to encourage

maintenance of high ethical standards” throughout the Army, because NCOs

function as “advisors to the officer and trainer, coach, teacher, counselor and

mentor to all ranks.” In his response to the proposal of Colonel Van Horn,

General Franks wrote his response in two sentences;

“Proposal

to establish William G. Bainbridge Chair of Ethics at the Sergeants Major Academy

is approved. Chair must represent ethical behavior demonstrated by SMA Bainbridge and serve to

emphasize role of noncommissioned officers in developing and maintaining those high

standards.”[14]

With

the approved proposal in place for the creation of the Bainbridge Chair in

Ethics, the study of military ethics became an authorized discipline of study

at the Academy. However, it soon became apparent that the ideals and duties of

the Bainbridge Chair could not be practically followed. Both the succeeding

Commandants and Command Sergeants Majors of USASMA were either unable or

unwilling to fulfill the teaching roles assigned by the creation of the new

chair. As the Academy continued to develop and mature into the preeminent

institution for training senior NCOs worldwide, the busy schedules of both the

Commandants and Command Sergeants Majors precluded any serious attempts to

fulfill the requirements of the Chair as originally intended. Additionally,

most of the Commandants and Command Sergeants Majors were not educated in

ethical theory, history and praxis. The annual symposium did not materialize

due to budgetary and time constraints as USASMA struggled to stay abreast of

demanding technologies and fulfill other requirements handed down from TRADOC.[15]

There

is some question regarding whether or not ethics was ever formally taught in

the years immediately following the tenure of COL Fredrick Van Horn. If a course

in ethics was offered, there seems to be no early standardization of what the

class was and how it was taught. [16] The

solution USASMA decided on to finally fulfill the conditions of the Bainbridge

Chair was to employ Army chaplains who had received graduate degrees in ethics

through Advanced Civil Schooling (ACS) and utilize them as Senior Ethics

Instructors. This solution answered another problem within the Academy. It maintained the presence of an Active Duty

Chaplain on the USASMA staff during a time when the reduction of personnel

through manpower assessments eliminated the chaplain slot altogether.[17]

USASMA

records indicate that chaplains were assigned to the academy beginning in 1973.[18]

But with the reorganization of Army assets and the creation of the Installation

Management Agency (IMA), now called Installation Management Command (IMCOM),

Unit Ministry teams (UMTs) comprised of a chaplain and a chaplain assistant

were no longer assigned to TRADOC schools.[19]

All chaplain support originated from the garrison where the school was located.

As a result, the ministry of a dedicated (assigned) chaplain could only be

obtained through the utilization of chaplains who were schooled through ACS to

teach ethics or world religions.[20]

Chaplains

assigned to USASMA provided some ethics instruction through limited, narrowly

defined roles. But those roles were often subject to change. In early 1987, the

school history records a “shift in the duties and responsibilities of the

chaplain”[21]

who had served as an instructor in the Leadership Division and a writer in the

Department of Training Development (DOTD) where lesson plans were developed. These lesson plans are called Training Support

Packages (TSPs) and serve to standardize training throughout the NCOES

worldwide.

Following

the Aberdeen Proving Grounds Scandal in April, 1997, ethics was taught by the

Academy chaplain as a required two hour block of instruction. [22] In 2004, the class on ethics was incorporated

into a TSP, providing a classroom guideline for discussions and small group

interaction. One of the requirements of the class was the writing of a three to

five page paper on an ethical issue by each student. These papers were competitively

read and judged through a committee comprised of the USASMA chaplain and other

qualified persons and remains a requirement within the Sergeant Major Course

today. The best papers are selected for the annual publication in the United States Sergeants Major Academy

Excellence in Writings Journal. Over the past few years, topics that have

received distinguished recognition include the following titles; [23]

Free

Speech and the Soldier’s Blog by MSG Rich Greene

Combat

Related Employment of Women by CWO Derek J.W. Bisson, Canadian

Forces

The

War On Terrorism and Transforming the Army by MSG Michael

Stout

The

Ethics of Processing Combat Deaths Under “Imminent Death” Regulations

by SGM Phil Pearce

The

Army’s Ethical Climate Since 11 September 2001 by

MSG Paul E. Coleman

Laying

the Ethical Foundation by SGM Daniel Hagan

The

Ethics of the United States Television News Media

by MSG Keith Preston

The

Problem With “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” by MSG Tabitha

Scrivens

Honor

or Revenge: An Ethical Dilemma by MSG Bryan K. Witzel

The

Christian in Combat by MSG Bart L. Culver

Torturing

the Enemy; Right or Wrong? By MSG Thomas L. Frances, Jr.

As

can be discerned from these titles the vast field of ethics, military life and

duty are fair game for study and debate by USASMA students. These topics illustrate

the number of important issues impacting military performance, efficiency,

effectiveness and well-being today. They are representative of the ongoing need

for ethics instruction within NCOES.

II. Transformation of NCOES and the Study of

Ethics-Where We’re Going

The

transformation of the NCOES into a more adaptable system of training and

education for an emergent military force structured to meet the challenges of

the 21st Century began in 2007. This has occasioned a thorough re-examination

of what and how we teach.[24]

With the entrance of Class 60 of the Sergeants Major Course a new era in class

design and instruction begins.[25] In 2009, Faculty Advisors (FAs) will be

designated as Instructor/Writers and will use curriculum adapted from the

Intermediate Level Education (ILE) coursework taught at the Command and General

Staff College (CGSC) in Leavenworth, Kansas. The purpose of this transformation

is to bring the NCO and Officer Corps closer together in their education and

training as leaders, while promoting a better understanding of the Army’s overall

operational and strategic concepts.

This

transformation will use an ethics package concurrent with what is presently

taught in ILE. This effort should promote an ongoing development in critical

thinking amongst senior NCOs. At least one ethics paper will continue to be

written by each student, and ethics as a topic of study will be squarely

located in classroom and lecture formats. The emphasis on reading, thinking,

debating and deciding will continue to characterize the USASMA approach to

ethical decision making. This begins with the Warrior Leader Course and is

designed to take soldiers beyond the standardized Basic and Advanced Individual

Training (AIT) modules where soldiers are first introduced to Army Values.

Other

methods of teaching ethics include the introduction of published authors and

guest speakers who specialize in topics that have ethical relevance to military

personnel.[26]

Through exposure to these persons, students are confronted with ideas that

often challenge hidden moral prejudices, and follow-on research and debate

ensue, contributing to the process of critical thinking. Programs involving

voluntary retreat formats also provide opportunities for ethics instruction.

Leadership off-sites, Bible studies, lending libraries and literature

distribution serve to keep ethical debate vibrant within the Academy. There are

discussions within the Academy about utilizing technology through podcasting to

further ethical training at the lower enlisted levels. Such programs would be

developed in concert with the web-based Self Structured Development Program

(SSDP) and be fed-out to squad level groups around the world.

Ongoing

research about how to introduce relevant, ethical dilemmas into simulated

battle-field training and exercises remains a focus of DOTD. An example of what

such a dilemma might look like includes a computerized training scenario where hostile

fire from a religious site housing innocent civilians occurs, and how soldiers

should respond. Another example students might encounter is the moral dilemma

of an oncoming vehicle that is visibly carrying children, but is in violation

of check-point protocols in a combat area, and whether or not to fire on the

approaching vehicle. Military personnel will continue to engage in small group

discussions and debates over such issues as killing a wounded insurgent who has

become incapacitated in a fire-fight or the detainment and treatment of

prisoners.[27]

Conclusion

Senior

NCOs increasingly recognize ethical dilemmas in the context of a Nation engaged

in an era of ongoing, persistent conflict with ideological enemies who often

have no nation-state allegiance. Yet, as stated at the outset of this paper,

the larger moral questions and responsibilities of our national leadership connects

to the ethical questions that place soldiers in harms way.[28] The

transformation of the Sergeants Major Course into a more synchronized program

of study with ILE should return many positive results in the near future. One

of these results will be the development of seasoned soldier-scholars who are better

equipped to do the right thing at the right time for the right purpose.

Teaching

military leaders to become ethical decision makers requires a program completely

integrated within the structured framework of NCOES where chaplains participate

as subject matter experts in ethical theory, history and praxis. The chaplain’s

seat at the table of NCOES development promotes the balanced evolution of

ethics within the military system where they can communicate values through the

institutions of church and state. Such ethics are based on faith, spiritual

fitness and those cherished traditions guiding the professional exercise of

military service. Ongoing involvement with ethical research, writing and

teaching is essential for this to occur. Through proactive engagement with the

relevant moral and ethical issues impacting the performance of duty and

accomplishment of mission, chaplains provide a viable conscience to the

management of violence.

As

our military is called upon to engage an ever-changing world with the possible

use of lethal force, we need to remain committed to training and educating

soldiers with those unchanging values

defining true military ethics. In so doing, we focus our quest for civilized

hope within the blur and blood of combat. In good conscience we can support our

Commander-in-Chief when the “duty to protect” is thrust upon our Nation and

American soldiers are called upon to deliver an answer.

Si vis pacem, para bellum

BIBLIOGRAPH

Dockery, Kevin, Future Weapons. New York:

The Berkley Publishing Group; 2007

Friedman, Thomas, The World Is Flat: A

Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, New

York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2005

Grossman, David, On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society. New York: Little, Brown and Company; 1995

Holmes, Richard, Dusty Warriors: Modern Soldiers At War. London; Harper Press, 2006

Huntington,

Samuel, The Soldier and the State:

The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations, Boston: President and

Fellows of Harvard University, Belknap Press; 15th printing 2000

Rejali, Darius, Torture and Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2007

Sanchez, Ricardo S., Wiser In Battle: A Soldier’s Story, New York: HarperCollins Publishers; 2008

Toffler, Alvin and Heidi, War and Anti-War. Survival at the Dawn of the 21st Century. New York: Little Brown and Company; 1993

Toner, James H, True Faith and Allegiance: The Burden of Military Ethics, Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky; 1995

Newspapers

and Journals

Abrams, David; Chair of Ethics allows NCOs to speak out for themselves. Fort Bliss Monitor, Ft Bliss, TX; April 6, 1995

Ferguson,

Mary; Future Combat Systems. The NCO

Journal, Volume 17, Issue 3, Summer 2008

Weigel, George; Dangling

Conversations: Posing the moral questions facing the next American president.

Newsweek Web Exclusive, October 6, 2008

United States

Army Sergeants Major Academy Excellence in Writings, Class 55, Class 56, Class

58.

United States Army Sergeants Major Academy, Ft Bliss, TX.

Web Sites

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/index.html

Global Security.Org

http//www.army.mil/aps/08/information_papers Persistent

Conflict

https://usasma.bliss.army.mil USASMA

Appendix-Colonel Fredrick Van Horn and General

Frederick M. Franks, Jr. Correspondence